A convenient index of this mini detective series.

In the first post of this series, we randomly chose a plant from the Kew Garden’s list of known Silverweed (Argentina) species. The particular species we landed on was Argentina sumatrana, whose sparse description neatly demonstrates the dearth of information available for most plant species in this genus (and indeed, if you were to pick a random unknown species, the situation would be very similar). We decided to go on a hunt to find out more about Argentina sumatrana - a description and a photograph.

In the second post, we discovered some of the scientists who dedicated their lives to classifying plants, with Argentina sumatrana being one such specimen. We found a species description but no photograph.

In the third post, we finally found a photograph of a very close cousin to Argentina sumatrana by combing through a compendium of field trips of Sumatra (in Indonesia).

In this final post, we close our case by tracking down a colour photograph of Argentina sumatrana (with some provisos).

We left the last post with a photograph of Argentina borneensis, a plant that looks very similar to A. sumatrana. What we would like to see is an actual photo of our suspect.

Back when Argentina sumatrana was originally classified as Potentilla sumatrana, we were told on page 222 that one of the specimens that Sojak used as a reference was given number 15216. I’ll repeat the whole line here

Sumatra, Atjeh, Gunung Leuser Nature Reserve: 10 km NE of kampung Seldok (Alas valley), de Wilde et de Wilde-Duyfjes 15216

As we already established, this specimen was picked on a field trip in 1975. On page 272, we see that an organisation called WOTRO in The Hague (Netherlands) sponsored Rijksherbarium, Leiden and Herbarium Bogoriense to undertake these trips.

Perhaps they have specimen number 15216 - it will have been a condition of the sponsorship that all photographs/specimens will have been submitted to at least one of these organisations. Beside, Sojak has definitely seen this sample. It must exist somewhere.

We are told that Rijksherbarium in Leiden (Netherlands) merged with two other herbaria to form one of the largest in the world (5.5 million species). Nowadays, the Naturalis Biodiversity Centre curates their collection. Let’s hit up their website.

Simply search for “Potentilla sumatrana” and you’ll see that there are 12 results. Surely one of these is our mythical number 15216.

The air is electric with tension!

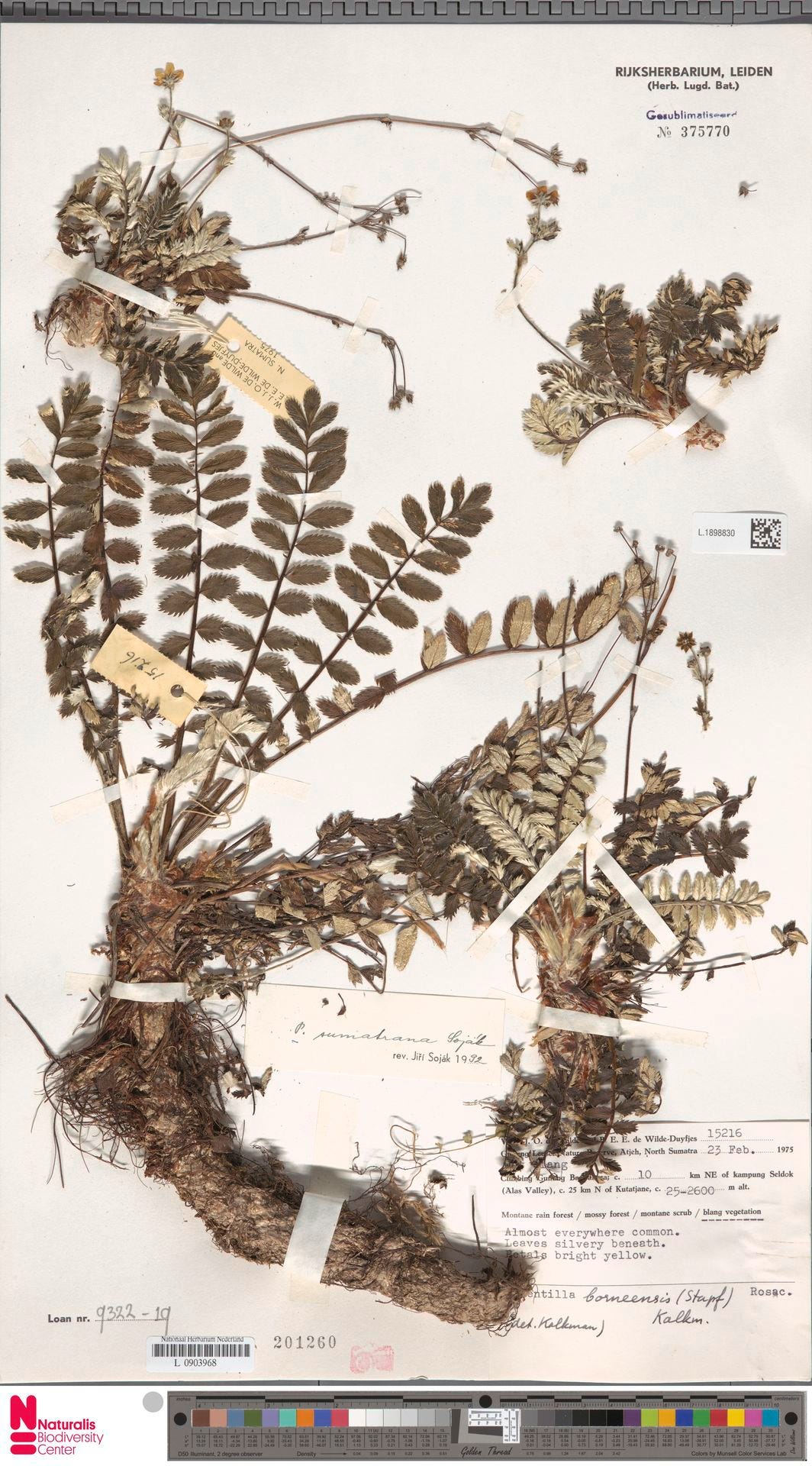

Click “L.1898830”.

Lo and behold!

We’ve found it! Specimen number 15216, and to be doubly sure, it was registered by the de Wilde duo in correct date range. In the previous article we had strong reason to believe that 15216 was found between 19th February and 5 Mar, and indeed we’re told that 15216 was found on the 23rd February. All the greatest hits are here, Sojak’s name appears in 1992 to tell us that this plant is not P. borneensis but P. sumatrana.

Together with the description we found in the second article and the photograph we found in the third article and now this full colour pressed specimen, we have likely have all the information we’re able to gather short of funding our own ethnobotanical expedition (Kickstarter campaign, anyone?).

Final Thoughts

Apart from feeling like I need a lie down in a dark room after this marathon series, there are some serious lessons to draw from this lighthearted journey.

As great as places like the Plants of the World Online are, the front page admits that less than a seventh of the plants listed have detailed descriptions, and just over a quarter of the plants have images. What a benefit to mankind it would be to have this database complete. Maybe I could tentatively submit my collated findings to POWO - though nothing new, it’s likely the first time image has met description in public - hard as that is to believe!

Now that we’ve trodden this journey once, we can take some short cuts. We now know that there are millions of photos from herbaria available online so we can jump there straight away for a good chance at a specimen image.

For descriptions, we need to become efficient at following citations and pray that none are hidden behind paywalls.

If I spent the next 30 years of my life uniting plant description and photo, one species a week, I wouldn’t scratch the remaining 1.2 million. We need some serious investment to complete this database within the next decade. Perhaps all it will take is a well considered academic software project, something an energetic PhD student or enthusiastic citizen scientist could accomplish.

Even after all this research, we still have little information. A taxonomic description and a photo is not enough. Perhaps A. sumatrana has potent medicinal properties, the next antibiotic, or thick and juicy storage roots, just waiting to be bred into the A. anserina line. We won’t know unless we obtain a sample and perform the appropriate tests. Dr. Quave talks about how even common plants have insufficient studies into their medicinal properties.

I started this series after finding it far too difficult to track down photo and description of a rare plant. I hope that my efforts will help others.