A convenient index of this mini detective series.

In the previous post of this series, we talked about how surprisingly difficult it is to find information about uncommon plants. In many ways, this process resembles detective work, though thankfully there is generally little nefarious activity at play.

We left the last article at a sign post. A botanist called Jiří Soják had a complicated on and off again relationship with the Argentina genus, and pointed (in cryptic abbreviated Latin) at another paper he wrote where he referred to A. sumatrana as Potentilla sumatrana:

A. sumatrana (Soják) Soják, comb. nova bas.

Potentilla sumatrana Soják, Preslia 64: 221. 1993 (“1992”).

Let’s pursue this suspect. Our trusty search engine tells us that “Preslia” is a journal published by the Czech Botanical Society. Luckily for us, it’s an open access journal. We can trace the journal down quite easily, now that we’ve been equipped with a citation guide. We are looking for volume 64, page 221 - remember, all this is relative to the journal, and the article itself was published in 1993 but was submitted in 1992.

As with all skills, the more you practice the faster and more comfortable you get. Citation trails like this are no different

I’ll link to the paper (annoyingly a PDF again, though some journals do use normal web pages nowadays as well) directly.

Do you feel that tingle in your fingers? Page 221 has something that at first skim looks like a description of our A. sumatrana. Linger on the text though, and you’ll quickly discover that it’s not in English! Luckily, we won’t be beaten by this. Pull out Google Translate (the hyperlink is to a URL shortener because the direct link to the Google translated text is too long), and it will automatically detect that this description is Latin. I’ll quote some of the text about the leaf:

Radical leaves 9-12-jugo-pinnate, sometimes intermittently pinnate in the upper part, 4.5-13 cm long.

Leaflets oblong-elliptical, running down the uppermost 1-3 yokes, the rest sessile, in the middle of the side l-2 x 0.4-0.8 cm large, with 6-9 sharp ± dense teeth on each side. 0.7-2.0 x 0.7-1.3 mm large.

Immediately below the Latin description is some comments about how A. sumatrana looks a lot like A. borneensis, but it doesn’t have the description.

What is going on here? It’s almost as though someone is actively stopping us from understanding the description. I can imagine a botanist cackling “you can find the description, but we never promised you could understand it!”. Jokes aside, it turns out that taxonomic descriptions were only accepted in Latin until 2012 - this is from the snappily named International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants. You can read the rule change (recommendation) of the previous revision (named the Melbourne code because the conference to decide this change was held there) of this code in article 39. The most recent code revision took place in 2017, Shenzhen, China, hence it is called the Shenzhen Code.

English translation notwithstanding, a lot of the text is still swathed in jargon. I doubt that the next conference will mandate something that is easily understood by the everyday person. I suppose it’s a lot easier to say “pinnate” rather than “feather-like” (not really).

So we have the description which we can unpick at our own leisure. Where is the photo? A paragraph buried at the very end of the Latin description gives us a clue

Specimens examined: Sumatra, Atjeh, Gunung Leuser Nature Reserve: 10 km NE of kampung Seldok (Alas valley), de Wilde et de Wilde-Duyfjes 15216, A; Atjeh, Gunong Kemeri, Iwatsuki, Murata, Dransfield et Saerudin 1278, K.

It seems that our friend Soják used two specimens to classify A. sumatrana. These two specimens were gathered by two teams, whose surnames we’ve been given as de Wilde and Wilde-Duyfjes, and Dransfield and Saerudin.

Dransfield appears to be Dr. John Dransfield who is an honorary research fellow at the Kew Gardens who specialises in Palms (Arecaceae). He must have taken some samples of A. sumatrana on the side whilst on a field trip to Sumatrana in 1971 to investigate Pteridophytes (ferns). In this botanical trip, Saerudin is mentioned as Didin Saerudin, Dransfield’s assistant.

I discovered that de Wilde and Wilde-Dufjes were an extremely productive husband and wife duo who collected around 25,000 specimens for herbariums. Their names were Brigitta de Wilde Duyfjes and Willem de Wilde. Sadly, Willem passed away just two years ago of lung cancer.

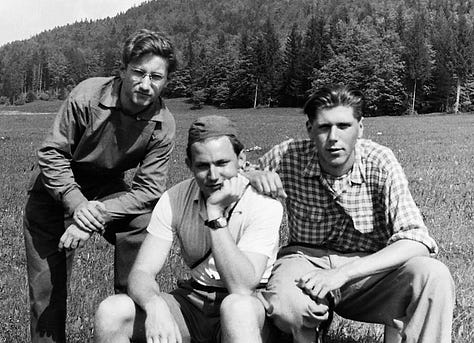

I also managed to locate an image of the steadfast Jiri Sojak from his university days in Prague in a heartfelt obituary.

If there’s one thing that will stick with me forever on this citation journey is the incredible stories of these plant hunters. Though they may just look like foot notes in the dusty electronic tomes of the internet hinterlands, each one carried a passion to find and document these plants for humanity.

For now, we’ll pause our botanical detective journey. We still don’t have a photograph of the A. sumatrana, but we’ll surely track it down in the next article!

For those going down a similar path, it might be worth mentioning sci-hub as a free resource for almost any research paper. Most published research was done by scientists working off government funding, who then have to often pay again so that for-profit journals can "publish" them. But that really means locking them behind exorbitant paywalls so the majority of the public (who originally funded the research) cannot read the papers themselves. Sci-hub is an important piece in the process of putting scientific research results back in public hands.