For your convenience, an index of this deep dive series, and also an index of my silverweed content.

This article took a surprising amount of time to write. I promptly fell down a deep rabbit hole of etymology, botanical history, ethnobotany - probably helped by my reading Cassandra Quave’s “Plant Hunter” book, and citation sleuthing. Just as a quick aside, Dr. Quave’s book is truly worth reading. A whole new room has opened up in my mind about the science and culture, and I’ve not even finished reading it yet!

Also, a special thanks to my proofreaders.

Potentilla nepalensis is more commonly known as the Nepal Cinquefoil. Nepalensis means “from Nepal” so this makes sense. The plants in the Potentilla genus are known as the Cinquefoils, because a lot of them have 5 palmate leaves - though this is meant to vary from 3 to as many as 15(!).

Location

The famous Kew Gardens entry has Nepal Cinquefoil isolated to Nepal, Pakistan and the West Himalayas. There is plenty of evidence that it is happy at a whole range of elevations, from sea level to 5000 m highland grasslands.

Description

If we may cite Wikipedia:

Potentilla nepalensis can reach a height of 30–60 centimetres (12–24 in). This plant forms low mounds of deep green strawberry-like leaves composed of broad leaflets. The cup-shaped 5-petalled flowers may be cherry red or deep pink, with a darker center, about 2.5 cm in width. They bloom July to August.

Cultivars

Beyond Wikipedia, a quick search of Potentilla nepalensis will net 5 common cultivars. For completion, here is a list of cultivars, maybe the first ever list on the internet - let me know if you have encountered others:

Helen Jane

Melton fire

Miss Willmott

Ron McBeath

Shogran

What’s in a cultivar

There is some evidence that the “Miss Willmott” cultivar is actually the unadulterated parent (first mentioned in scientific literature in 1924), and by luck this is the cultivar I purchased (because it was the cheapest). On the other hand, after delving deeper, any species cultivar called “Miss Willmott”, “Ellen Willmott” or “Willmottiae” is named after the famous horticulturist Ellen Willmott. Someone has thought about this too and found references from as early as 1909.

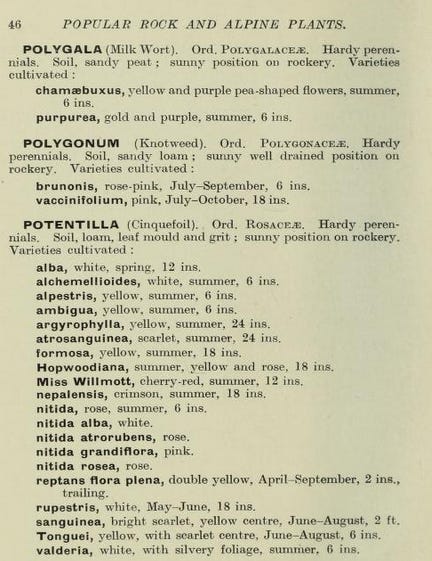

According to the “Popular Rock and Alpine Plants” from 1916 (see above image), the “Miss Willmott” variety is “cherry red” and shorter than the parent, which is crimson.

To end this tangent, my hypothesis on what has happened is this. Potentilla nepalensis was first published in literature in 1824, well before the birth of Ellen Willmott in 1858. As she rose to horticulture fame, someone bred or discovered a P. nepalensis seedling of slightly different colour and lower form and named it after the star of the day. This was first mentioned in 1909 when Miss Willmott was at the height of her fame. Later on in 1924, as she experienced some financial troubles, a scientific book mistakes Potentilla nepalensis var. Willmottiae for the unadulterated parent. I was unable to find an online source of this book, but I did find a plant directory in the same year which specifically lists the cultivar alongside the parent.

This time, the “Miss Willmott” cultivar is known as “Willmottiae”.

We probably have sufficient evidence to show that “Miss Willmott” is not the original P. nepalensis.

Comparison to Silverweed

Petals

If you ignore the colour, Silverweed and Nepal Cinquefoil have very similar flowers. A potentilleae characteristic I’ve noticed is the 20 stamen surrounding a stigma cluster. The petals of the Nepal Cinquefoil are more obcordate (heart-shaped) whilst the Silverweed petals are obovate (teardrop shaped).

Leaves

The leaves of P. nepalensis basically bear no resemblance to A. anserina. In fact, I’ve seen it called Strawberry potentilla for that reason in older literature. The silverweed leaves are described on Wikipedia as

10–20 cm long, evenly pinnate into in saw-toothed leaflets 2–5 cm long and 1–2 cm broad with 6 - 14 teeth per side, covered with silky white hairs, particularly on the underside […] These give the leaves the silvery appearance from which the plant gets its name. Each leaf is borne on a channeled petiole up to 5cm in length with a long sheathing base.

whereas I think the Nepal Cinquefoil is best described as

Strawberry-like, 5-palmate leaves 8-10cm (3-4in) long

Medicinal Qualities and Edibility

Less “Westernised” cultures often do not make the distinction between the consumption of calories and eating for the health of the body. The two are intertwined intimately in their culture and diet. So we will talk about both in the same breath. In this sense, this section is taken from an ethnobotany angle.

Ethnobotany simply means ... investigating plants used by societies in various parts of the world.

A famous example of this would be the discovery of an anti-malarial drug from traditional Chinese medicine.

It may be tempting to write off the efficacy of “herbal” remedies in this context, but western society has been mining this rich seam for a long time. Other examples include aspirin and a chemotherapy medication called Vincristine.

From here, we dive off the deep end into obscure papers and references.

I am not asserting that Nepal Cinquefoil has the benefits described below, but it is worthy of investigation, just as Cassandra Quave investigated the elmleaf blackberry plant

The earliest published record of the medicinal qualities of P. nepalensis is the absolute tome “A Dictionary of the Economic Products of India” by a Scottish botanist called George Watt. Luckily, Google Books allows you to read this book. It has this to say about the Nepal Cinquefoil (page 332)

Dye - The reddish [root] is said […] to form part of dye-stuff and medicinal root exorted under the name of rattanjot. It is employed to impart a red colour to wool.

Medicine - Rattanjot is considered a depurative and is “used externally in the Yunani system, the ashes being applied with oil to burns” […]

Wool dyes aside, a depurative is ritually purifying or able to remove toxic chemicals from the body.

As well as aiding burn injuries, the roots have been used to heal cuts and general wounds.

Last year, a study came out which found antimicrobial and antioxidant properties in the shoots of Nepal Cinquefoil.

From a limited access journal, I was able to piece together that Nepal Cinquefoil leaves are used to brew a liquor.

I also found a reference to P. nepalensis being used to heal dog bites by the local people of the Tons Valley Region in the Uttarkashi District of the Northwest Himalayas, India.

Why I chose P. nepalensis

The original reason why I decided to try and breed P. nepalensis with A. anserina is due to a terse reference from the excellent Plants for a Future database:

Root - cooked. Starchy

If we trace the reference, we arrive at a book that I have not been able to locate online called “Plants for human consumption” by the late German botanist called Günther W.H. Kunkel. I would like to get a hold of this book so I can see if Dr. Kunkel cites anything for this statement. In any case, I will prove this when I cook up some roots to try in the autumn!

Intergeneric Cross Predictions

Now we are onto the home stretch, and a fun one at that. What will an intergeneric cross of P. nepalensis and A. anserina even look like? Is it even possible?

Well, a few days ago, I discovered that two scientists tried a bunch of crosses between different species in the potentilleae tribe! Alas, the combination I was looking for was not attempted, but I will certainly bring up the combinations of note when I deep dive into other species like P. recta.

Just as a sneak peak, they did not find many viable crosses, but their sample size is so small (about 30) that I might even say it’s statistically irrelvant to make any conclusions, especially if you compare to Luther Burbank’s 10,000 or more seedlings per generation.

Note also that not so long ago, silverweed and Nepal Cinquefoil were in the same genus, and people would not have batted an eyelid at the crossing attempt.

Anyway, let’s guess. Let’s assume the cross is possible, and we are able to stabilise the later generations so that they breed “true”.

Leaves - strawberry-like but silver, and more leaflets.

Flowers - orange, very lightly heart shaped

Growth habit - vigorous and mounding

Climate preference - from damp water courses to high altitude meadows

Edibility - starchy roots, brew-able tea from the leaves

Medicinal properties - a rich range of health benefits, including healing skin ailments and promoting gut health

Here’s hoping that the cross is successful. I don’t mind if my predictions are way off, it’s just fun to try!