In my last post, I tried to persuade you that Cotoneaster was worthy of being the next food staple. I also talked about some possible dangers that we will need to head off.

Now that we have the whys and pitfalls out of the way, we can talk about various methods to go about achieving our stated goal:

The goal is to breed a Cotoneaster that is particularly large and long lasting, which can be used as a food staple in the same way as a potato.

Cotoneaster is already long lasting, thanks in no part to its higher than average cyanogenic glycoside content. What we need to do is fatten up the fruit so that its not a laborious effort to harvest an appreciable amount.

I’ll lay out the plans that I have been pondering through this dark and wet British winter.

Interspecies hybrids

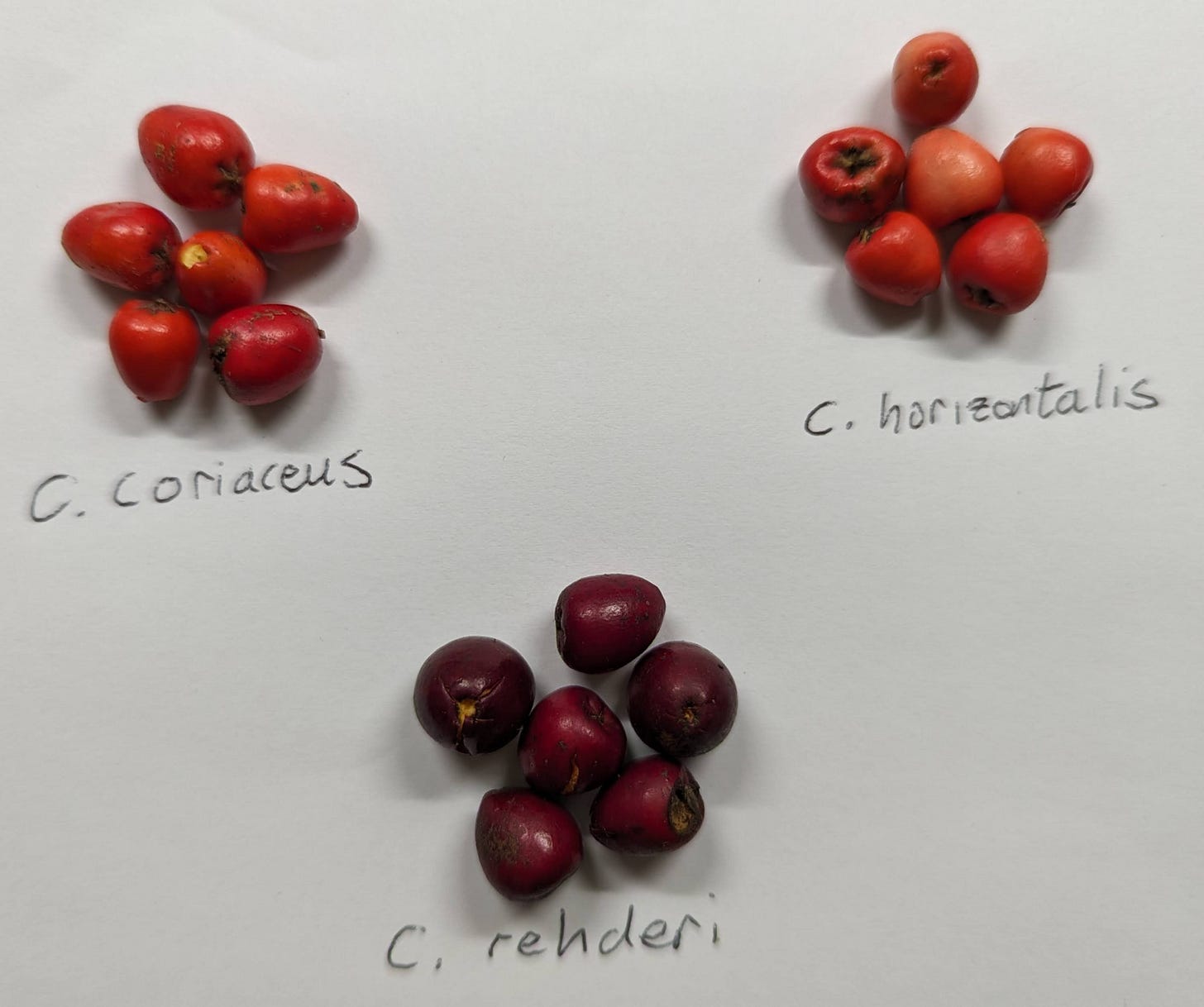

On a rare dry winter, I ventured out into the neighbourhood and collected various wild Cotoneaster species. I ignored specimens planted for ornamental reasons - I’m after the strongest and most rugged genes. I found a tree-like Cotoneaster growing behind my local doctor’s office. Next, I found the wreckage of a shrub-like Cotoneaster growing in some waste ground next to a sports field. And finally, a tough looking shrubby Cotoneaster in the alleyway behind the local convenience store where workers have their smoke breaks.

You’re wondering why I didn’t give the Latin names.

Cotoneaster is notoriously promiscuous - that is, they breed across the species barrier like you and I cross the road. The situation is similar, but not quite as bad as Rose classification. I’ll quote the relevant Wikipedia article as it makes me laugh (emphasis my own):

The numbers 320 to 350 are the figures accepted by most botanists, but […] the extreme lumpers Bentham and Hooker only allowed for 30 species, while the extreme splitter Michel Gandoger allowed 4,266 species just in Europe and West Asia.

If you want iNaturalist’s best guess, then the tree-like Cotoneaster is probably C. bullatus, the one next to the sports field is likely C. coriaceus and the one in the smoking alley defeats machine learning and volunteer alike (probably something in the “Alpigeni” section, a section being a group of species that share common traits).

All this to say, I don’t really know what species these collected Cotoneaster species are, but they’re at least able to survive and fruit in pretty tough conditions.

Perhaps you can see the plan now.

It’s simple: grow out these Cotoneaster species and cross them when they flower, plant the seed from the fruit and repeat, choosing the largest fruit all the while.

Intergeneric hybrids

Intergeneric hybridisation is the speed run version of plant breeding. Smash together two plants that belong to the same family but different genus and see what wild and whacky offspring burst forth.

This is another plan I’ve been thinking of.

Source the largest fruiting Cotoneaster (this is C. bullatus as far as I can tell) and cross it with another member of the Rosaceae family. Ready-to-flower Bullate Cotoneaster is easy and cheap to source thanks to the ornamental plant industry.

But which Rosaceae species? There are almost 5000. Of that large number, we can prune the candidates down to those that are cheap and easy to source, and from there we can trim still further by those that are known to leave fruit on the branch well into winter. After all, we don’t want to lose this trait. Throw that criteria into the blender and further strain it for edibility and large fruit size and we end up with one category of candidates: undomesticated apples.

I’ve discarded Malus domestica straight off the bat as they are highly inbred. Even though their fruit is extremely large, their febrile nature is the price they pay - we don’t want those genes in our offspring.

What we are left with is any other species in the Malus genus. Around here, crab apples are embarassingly easy to source and we are even helped with useful descriptions for specific cultivars such as “keeps fruits long into winter”.

So that’s the plan: create intergeneric hybrids between C. bullatus and an undomesticated Malus species.

Let’s end on a replay of the story from the previous article to remind us what we’re shooting for

The nights are getting longer now, and you’ve decided it’s time to light the fire. The roast is almost ready, another quarter of an hour should do it. You fancy a change from potatoes today - the harvest was pretty good but it can get monotonous - so you step out into the back garden with a wicker basket. You walk over to a shady spot where you planted a beautiful Sharavo Tree several years ago. You ordered this cultivar from your local food forest nursery, who provide robust grafted trees to anyone for a reasonable price.

The “Sharavo” was just one of the Cotoneaster cultivars on offer, another being “Xinan”. You recall the nursery owner telling you that these are local names, names of parent species that have intermingled their genes to create these delicious offspring and were themselves eaten by peoples in Asia. The owner said that this was a great way to honour those people and to carry on their traditions, and you found yourself agreeing whole-heartedly.

Apple sized fruits hang like red baubles from the elegantly arching herringbone branches, and you pause to admire the scene. A couple of Sharavo fruits each should suffice and you pluck them, one at a time, placing them lovingly in your willow wicker basket.

Back inside, you grate the red fruits and boil the mash in a little water for a ten minutes. A fragrant and subtle apple scent wafts into your face. You add a little seasoning into the Sharavo mash and place generous dollops onto some flat plates.

Time to carve the roast.

Who knows, perhaps we can make it to the Sharavo Tree in one giant leap.

Final Thoughts

What do you think about my plans? Is there something I’m missing, another more promising Cotoneaster I should be sourcing instead? Please let me know in the comments.

Talking about number of species, there are some 264 recognised cotoneaster species which is an appreciable fraction of all Rosaceae species (about 5000)!

In related news, I found one place on the internet that is selling C. nummularius seed, so of course I thunked the buy button straight away. I’m not letting the only Cotoneaster species with a nutritional analysis get away from me.

Until next time.

Hello, evolutionary biology student here. As far as I'm aware, there's existing crosses of Sorbus and Cotoneaster, and there is a very large fruiting Sorbus variety here in Czechia, Sorbus Domestica (of unclear origin, perhaps Sorbus+apple cross? Who knows) which could perhaps be crossed with Cotoneaster. however sorbocotoneasters that do exist don't produce very fertile offspring, therefore need to be grafted as a clonal cultivar. I'm also thinking of crosses with quinces (Cydonia oblonga), Mespilus and perhaps most interestingly Amelanchier (which is known to be able to cross with Sorbus)

I see that there have been intergeneric crosses between the Sorbus genus and Cottoneaster. Also Sorbus and pyrus as well as with Medlars. I saw other crosses listed, but these three stood out.

Perhaps you could use some of these intergeneric crosses or make your own. Then cross with each other.