Part of my series on hidden edible treasures of the ornamental plant world

Disclaimer: Please do your own research and consult knowledgeable people in your area before eating anything I talk about on this substack.

Just to be clear, when I say Cherry Laurel, I am referring to Prunus laurocerasus. There has been some confusion with Prunus caroliniana which is also confusingly referred to as (Carolina) Laurel Cherry or just Cherry Laurel in the US. I am not referring to P. caroliniana in this article, but P. laurocerasus.

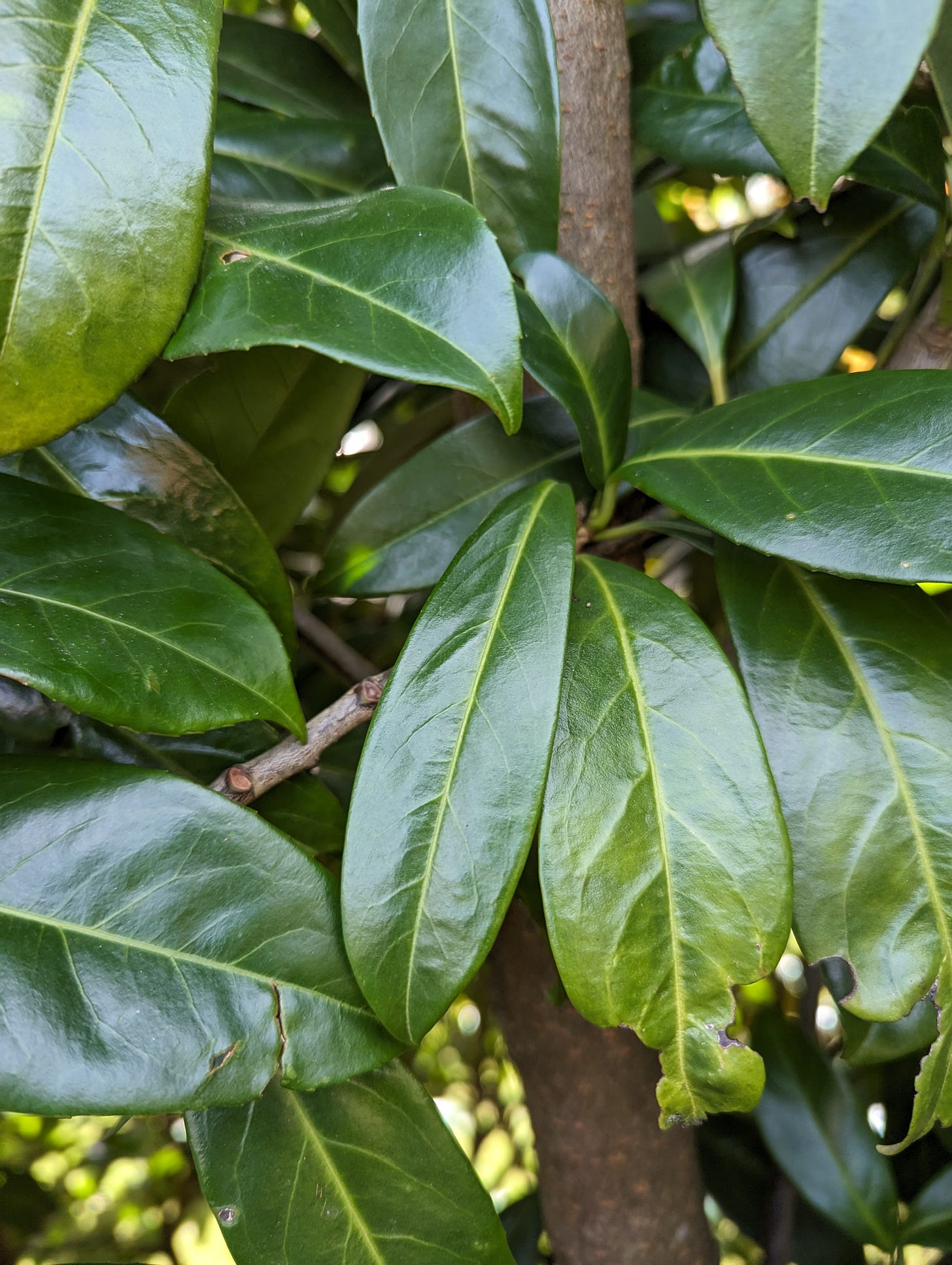

I became acquainted with the infamous Cherry Laurel over a period of years. On the other side of my North facing fence is my neighbour’s thick stand of Prunus laurocerasus. It’s an excellent, fast growing, privacy hedge for her. This cuts both ways, as now I have even less light coming through to my garden and also need to battle a thick root mat in which younger plants struggle to establish.

If I dig down a couple of shovel heights there’s a very clear dry layer, which always blows my mind given the high amount of rainfall I receive in this area. Obviously the slow steady rain is stolen away by the Cherry Laurel before having the chance to permeate into the subsoil.

In the early spring of this year I finally decided to take drastic action (no, I didn’t cut down the hedge in the middle of the night). I went down the whole side of the fence with a saw, hacking off the root mat at my boundary. Then, I hammered deep holes throughout the bed and filled them with my home made compost - worms included. Hat tip to

for this idea. It’s an interesting exercise in context in light of the recent “no-dig” gardening paradigm shift.The egocentric part of me likes to think that my intervention caused the resultant abundant plant growth, but Nature, as usual, will quietly smile and keep her secrets.

Someone clearly has beef with the poor Cherry Laurel, the Wikipedia article notes it as “invasive” in different regions though the citations are poor. You’ll do a lot better with a Google Scholar search. Apparently the problem is that Prunus laurocerasus out-competes native species, changing the soil composition with its aggressive root systems. To add insult to injury, the seed is spread widely by birds that feast on the fruit.

On the face of it, my research told me to abhor the Cherry Laurel, but I decided to dig deeper after spotting a few sources that spoke of their edibility.

Initially sceptical, I’ve become converted to the greatness of Cherry Laurel and slightly outraged with their chronic under-use in food forests.

Let me rewind, and I’ll explain.

The Cherry Laurel, Prunus laurocerasus, is very much an under appreciated species in the Prunus genus. It’s the trouble child that the famous relations hate to mention. You will be familiar with these rock stars of the Prunus world: cherries, plums, apricots, peaches and almonds.

Open any respectable food forest book and there will be many recommended Prunus species. What you won’t see is a recommendation to plant and eat the fruit of the Cherry Laurel. This is because they are widely known to be toxic; ask a random person off the street and they’ll tell you that the Cherry Laurel fruit is poisonous (and probably any other street side fruit, like Hawthorn…).

Thankfully, the people living in the Eastern Black Sea Region of Türkiye don’t care about the news from the street. They eat Karayemiş - what they call the Cherry Laurel fruit and literally and confusingly translated as Blackberry - straight from the branch, dried, pickled, as jam, stewed fruit, roasted, in cakes and more.

Luckily for us, the Turkish do not have some genetic predisposition to toxic berries. As is often the case, the truth is more nuanced.

The Cherry Laurel plant contains a compound called cyanogenic glycoside in its seeds, leaves and fruit. When the plant is attacked (with for example, your digestive system during a mid day snack), the cell walls of the plant are broken and release an enzyme that digests the cyanogenic glycosides and cause it to release a previously inert form of hydrogen cyanide.

Hydrogen cyanide is generally bad news. It was used in World War I as a chemical warfare agent, and in Nazi concentration camps. Even now, it’s being employed as an agent in judicial execution in the USA. Hydrogen cyanide is an effective airborne method of inflicting cyanide poisoning.

So it’s clear that we don’t want to get our facts wrong, and it’s also clear that the Turkish have the facts right. What gives?

Digging deeper, we find that the cyanogenic glycosides present in the Cherry Laurel fruit are initially very high when under ripe. As the fruit ripens, it drops down to zero when ready for consumption. This is a useful evolutionary survival trait. From the perspective of the Cherry Laurel plant, it’s beneficial to put off any over-eager seed distributors. They’re saying, “you’ll eat our fruit when we’re good and ready, not when you are.”

We can tell that it’s a helpful, rather than sinister, adaption because hydrogen cyanide tastes bitter, with almond tones. If the Cherry Laurel were out to get us, it would have no taste. To me, this is a double edged sword because I absolutely love the almond flavouring in marzipan.

The lesson is clear here, the fruit will tell you when it’s good and ripe.

If you don’t want to wait, then you can process the cyanogenic glycoside away by drying, fermenting or cooking, much as the cassava is made human safe.

Consumption aside, there are a myriad medicinal benefits associated with Cherry Laurel, including but not limited to: treating digestive complaints and eczema, and the high phenol concentrations are likely effective in cancer prevention, neurodegenerative diseases and more.

It’s become clear to me that Prunus laurocerasus has been much maligned. The most common complaint is the toxicity, but there’s no reason folk knowledge can’t be integrated into our every day lives. After all, everyone knows that eating a green potato, is a big no no. Why should the fruit of the Cherry Laurel be any different?

The Cherry Laurel fruit orchard industry is very much in its infancy. The number of cultivars of a species is always a good rule of thumb for this. Improved fruiting variants include “Kiraz”,“Fındık” and “Camelliifolia”. Compare this to 247 cultivars of Sweet Cherry, Prunus avium (there are likely more) - there is much work to be done!

My neighbour’s Cherry Laurel is a reliable, prolific bearer of succulent black fruit. With the current trend of bizarre weather, can we honestly afford to turn our noses up at this maintenance free prodigal son of the Prunus genus?

Final Thoughts

If you fancy creating a new Cherry Laurel cultivar, the bar is pretty low. Start planting the seeds of tasty cultivar. They apparently need cold stratification and might take more than one growing season to germinate. Once you’ve found a great tasting cultivar, and bonus points if it bears prolifically, you can propagate them from mature cuttings and give it a cool sounding name!

Let’s lay down all the desirable features of Prunus laurocerasus in one place: fruits in the shade, beautiful flowers, vigorous, evergreen, easily propagated from cuttings, survives down to -10°F (-23°C) - USDA Zone 6, RHS Hardiness H5. Try and find another tree that can match those features!

P. laurocerasus is known to be invasive in different regions, so weigh up in your mind your position on this. Personally, I would rather a living hedge than an artificial fence, and since there’s many miles of it in my region (UK) already, I might as well take advantage of the free fruit!

I’m having a lot of fun with this little series of undiscovered food forest gems. Let me know if there are other plants that you think deserve a spot light.

Until next time.

Bibliography

An excellent entry in the Useful Temperate Plants database about Cherry Laurel which talks about a prolifically bearing variety called “Camelliifolia” as well as propagating techniques

“Fındık” is another cultivar listed to be particularly good for consumption

A spotlight on the “Kiraz” cultivar

A list of 11 cultivars in Türkiye

A useful review of the use of Cherry Laurel as a food crop in Türkiye

Orchard level quality of Cherry Laurel is in infancy

A heroic attempt at analysing the genotypes of P. laurocerasus for future breeding work

P. laurocerasus is also sometimes described as Laurocerasus officinalus

Medicinal qualities of Cherry Laurel

Evidence that there is a high degree of genetic diversity for future breeding projects

Novel use of Cherry Laurel fruit to make Komubcha

Methods to remove cyanogenic glycosides from food

A study that demonstrates that cyanogenic glycoside content in Cherry Laurel fruit decreases to trace amounts in ripe fruit

A paper that discusses how P. laurocerasus takes in a lot of soil moisture

I bring 21 seeds from Turkey recently. I am going to place it in frigde for cold stratification and hopefully get some plants.

Thanks a lot for the great article. I learned a lot. Would be interesting to trial the Turkish varieties in different parts of Europe.